The White Horse, Prior's Dean, or The Pub With No Name.

This Saturday, 19th September 2015.

The Edward Thomas Fellowship has organised a tremendous event to celebrate the pub which was the setting for Edward Thomas's first poem.

The inn, as Thomas would have called it - is the Pub-with-no-name near Froxfield and Prior's Dean, but really near nowhere at all. It is a comfortable walk from Steep and the subject of his first known poem, Up in the Wind.(3rd December 1914).

|

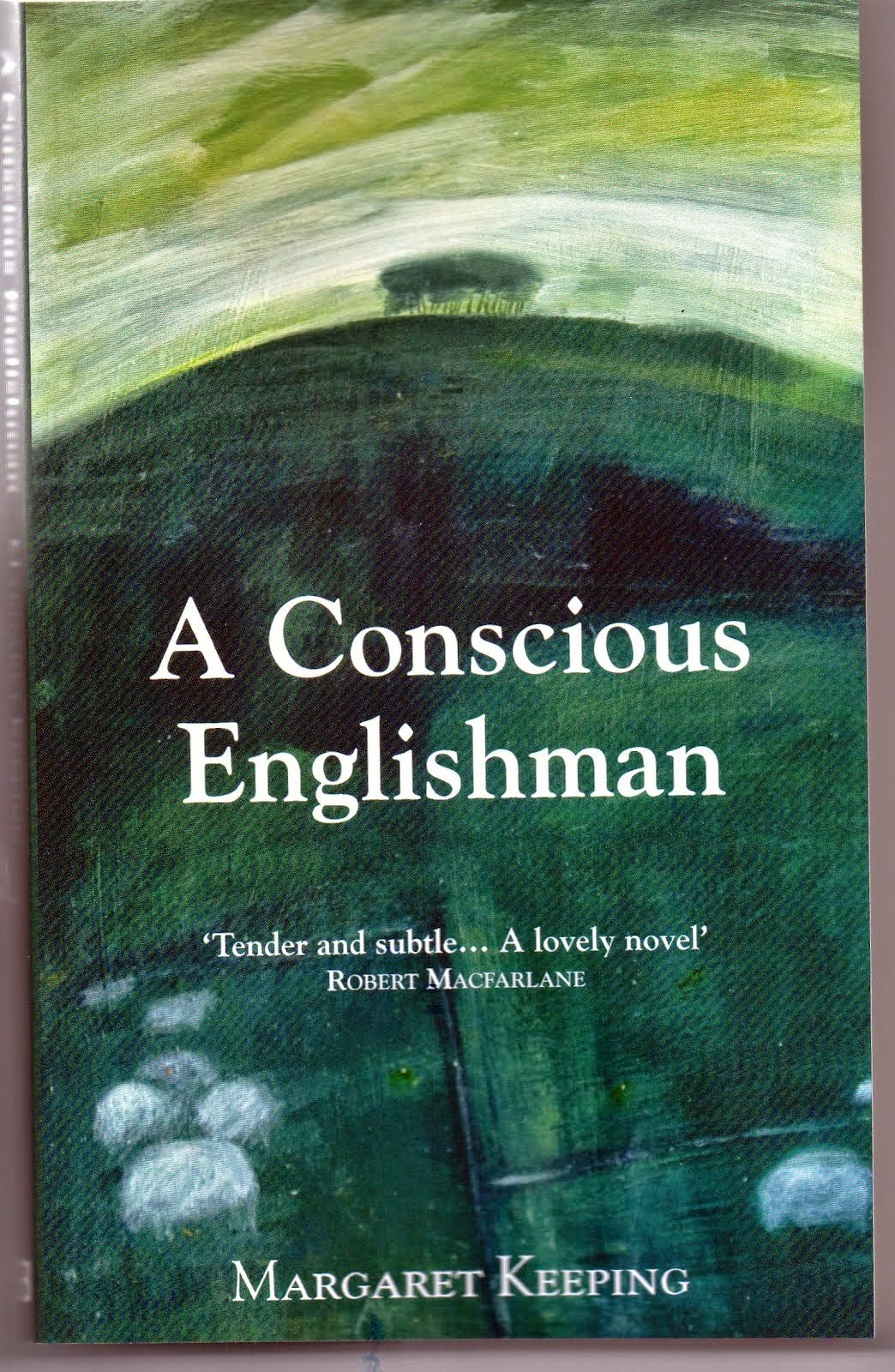

| The Pub with no name - the inn sign frame remains blank. ( Its name is The White Horse)

|

"Tall beeches overhang the inn, dwarfing and half hiding it, for it lies back a field’s breadth from the by road. The field is divided from the road by a hedge and only a path from one corner and a cart track from the other which meet under the beeches connect the inn with the road. But for a signboard or rather the post and empty iron frame of a signboard close to the road behind the hedge a traveller could not guess at an inn. The low dirty white building looks like a farmhouse, with a lean-to, a rick and a shed of black boarding at one side . . . "

As Edna Longley writes, "Up in the Wind is Thomas's closest approximation to the Robert Frost "eclogue" in which rural speakers tell or act out their story." Her annotation to the poem adds so much to the reading of it.

The event is open to the public, but the lunches, including the 'Edward Thomas sausage', are already booked. There is to be a strenuous walk beginning at 10 15 from the pub, lunch and the dedication of a bench to Thomas. In the evening Pedal Folk and others are performing at Steep.

Here is the beginning of the beginning of the poem, but not the version we know. It is an early draft from the Oxford digitalisation project, full of too much verbiage but giving an insight into the place and the process. Don't ask me why, though on screen it is laid out with enjambments, when you copy and paste they are lost! The capital letters help you find your way and in this case I find it interesting - half note-book, half poem.

UP IN THE WIND by EDWARD THOMAS

'I could wring the old thing's neck that put it here!

A public-house! it may be public for birds,

Squirrels, and suchlike, ghosts of charcoal-burners

And highwaymen.' The wild girl laughed. 'But I

Hate it since I came back from Kennington.

I gave up a good place.' Her Cockney accent

Made her and the house seem wilder by calling up---

Only to be subdued at once by wildness---

The idea of London, there in that forest parlour,

Low and small among the towering beeches,

And the one bulging butt that's like a font.

Her eyes flashed up; she shook her hair away

From eyes and mouth, as if to shriek again;

Then sighed back to her scrubbing. While I drank

I might have mused of coaches and highwaymen,

Charcoal-burners and life that loves the wild.

For who now used these roads except myself,

A market waggon every other Wednesday,

A solitary tramp, some very fresh one

Ignorant of these eleven houseless miles,

A motorist from a distance slowing down

To taste whatever luxury he can

In having North Downs clear behind, South clear before,

And being midway between two railway lines,

Far out of sight or sound of them? There are

Some houses---down the by-lanes; and a few

Are visible---when their damsons are in bloom.

But the land is wild, and there's a spirit of wildness

Much older, crying when the stone-curlew yodels

His sea and mountain cry, high up in Spring.

He nests in fields where still the gorse is free as

When all was open and common. Common 'tis named

And calls itself, because the bracken and gorse

Still hold the hedge where plough and scythe have chased them.

Once on a time 'tis plain that the 'White Horse'

Stood merely on the border of waste

Where horse and cart picked its own course afresh.

On all sides then, as now, paths ran to the inn;

And now a farm-track takes you from a gate.

Two roads cross, and not a house in sight

Except the 'White Horse' in this clump of beeches.

It hides from either road, a field's breadth back;

And it's the trees you see, and not the house,

Both near and far, when the clump's the highest thing

And homely, too, upon a far horizon

To one that knows there is an inn within.

British Trust for Ornithology.

British Trust for Ornithology.

Saxon/Norman Aldbury 'neglected old church ....too much like a shameless unburied corpse.' Maybe he didn't like the 19th cupola that replaced a spire.

Saxon/Norman Aldbury 'neglected old church ....too much like a shameless unburied corpse.' Maybe he didn't like the 19th cupola that replaced a spire.