Edward Thomas and Oxford

As I live in Oxford and have lived in or around the city since the mid-sixties it is important to me and I believe it was important to Edward Thomas, but he did not have a care-free time at University. He left school at just seventeen, his father insisting that he studied at home for Civil service entrance, but instead he set off to walk from London to Swindon, taking notes for the book that became A Woodland Life. He'd already had a dozen articles published in national journals and was earning money from them; this gave him courage to stand up to his father and the Civil service idea was dropped - instead he was to apply to Oxford.

He had been encouraged in his writing

by James Noble, writer and critic and father of Helen. Helen and Edward fell in

love, and on her twentieth birthday became lovers. Biographers agree that for

young people of their class this was not usual - some query Helen's motives, I

think she was a very passionate person.

In the autumn of 1897 he went up to

Oxford to work for a scholarship while

living in lodgings at 113 Cowley

Road, as a non-collegiate student.

If you're not familiar with it, today

Cowley Road qualifies for the word 'vibrant' - restaurants, bars, shops of

every ethnicity, a live music venue, small independant cinema, a well-known

early health-food shop, Uhuru, very trendy community market - so much I can't

begin to describe it.

East Oxford overall is also becoming the creative heart of

Oxford, especially though not entirely, for younger artists and writers.What it's not known

for is its architecture or for more established literary connections (Gerard

Manley Hopkins referred to East Oxford as Oxford's 'base and brickish

skirt'.)

Not like North Oxford which is peppered with blue plaques.

I would very much like to see the house, 113, marked in some way. A young stone-mason, Richard Morely, happened to be living there, and we talked about the possibility of doing something, with the help of the Edward Thomas Fellowship. (Richard remains in Oxford and can be contacted for commissions - morleymasonry@hotmail.com)

The wording was agreed and a design made, but it is on hold at the moment.

Oxford 'Entrance'

Not like North Oxford which is peppered with blue plaques.

I would very much like to see the house, 113, marked in some way. A young stone-mason, Richard Morely, happened to be living there, and we talked about the possibility of doing something, with the help of the Edward Thomas Fellowship. (Richard remains in Oxford and can be contacted for commissions - morleymasonry@hotmail.com)

The wording was agreed and a design made, but it is on hold at the moment.

Oxford 'Entrance'

The non-collegiate

scheme was not unlike the set-up in which I took my B.Ed, and Edward was not

going to be satisfied with it. He had to pass exams in Greek, Latin and logic

with Mathematics, and failed three times to pass what was in effect the Oxford

entrance exam. He went to lectures in the morning, walked in the afternoon,

worked for the rest of the time.

Edward wrote very

loving letters to Helen almost daily,

'I am very happy

with you, very content, and very hopeful.... you alone are beautiful. I can

often doubt whether what I see is beautiful; but I know....{unfinished}

He

took long walks into the country - 'Late flights of larks were singing and

darting about in the last gardens of the town and the first fields of the

country.' -,wrote 'verses' and

wanted her opinion, asking if she thought them ludicrous. He treated

her as an intellectual equal at that time, suggesting reading they could

discuss later.

Many letters are sexually charged, and one refers to the rights

and wrong of 'preventatives' - contraception. In others Edward is distinguishing

lust from love, saying that love lasts and also allows room for other things,

whereas lust is obsessional and allows room for nothing else.

As always though, he worked hard and

eventually won the history scholarship he needed to go to Oxford 'proper', to

Lincoln College to read history.

There was of course

no such thing as 'English literature' in conservative Oxford; it carried an

association of dissent and belonged in Liverpool and London. But it's clear

that Edward spent a good deal of his time reading literature, for pleasure and

because he was still selling his articles to journals.

|

| The Turl |

From The

Word, (which goes on to concern something quite different from the

formal learning at its beginning):

From The

Word, (which goes on to concern something quite different from the

formal learning at its beginning):

From THE WORD.

There are so many

things I have forgot,

That once were much

to me, or that were not,All lost, as is a childless woman's child

And its child's children, in the undefiled

Abyss of what can never come again.

I have forgot, too, names of mighty men

That fought and lost or won in the old wars,

Of kings and fiends and gods, and most of the stars.

Some things I have forgot that I forget.

And here is part of a poem from

Branchlines, Edward Thomas and Contemporary Poetry, edited by Guy

Cuthbertson and Lucy Newlyn, in which fifty-three of today's poets respond to

him in their own work.

This is Robert Crawford on a sense of

his presence in Oxford still; Guy, his former student, is the man the poet met

by chance, and certainly for me 'Your man, Edward Thomas,' is exactly right.

That is Guy, and an ever-helpful guide and clue-dropper to me.

The second stanza is about the collection of letters between Edward and Robert Frost, 'Elected Friends', edited by Matthew Spencer.

The second stanza is about the collection of letters between Edward and Robert Frost, 'Elected Friends', edited by Matthew Spencer.

E.T.

'somehow someday I shall be here

again'

When we met by chance on the Turl,

were you awareYon door opposite was exactly the dark door where

Your man, Edward Thomas, before he became a poet,

Nipped out of the world and into Lincoln College?

Odd we met and spoke about him there.

Odd, too, in St Louis, seeing in the Left Bank bookstore

That

book of his to-and-fro with Robert Frost.

I bought it on impulse - his finest

writing

So lightly right I can't get away from him,

Though all the time I

know he isn't there.

Any comments about the plaque idea would be very welcome.

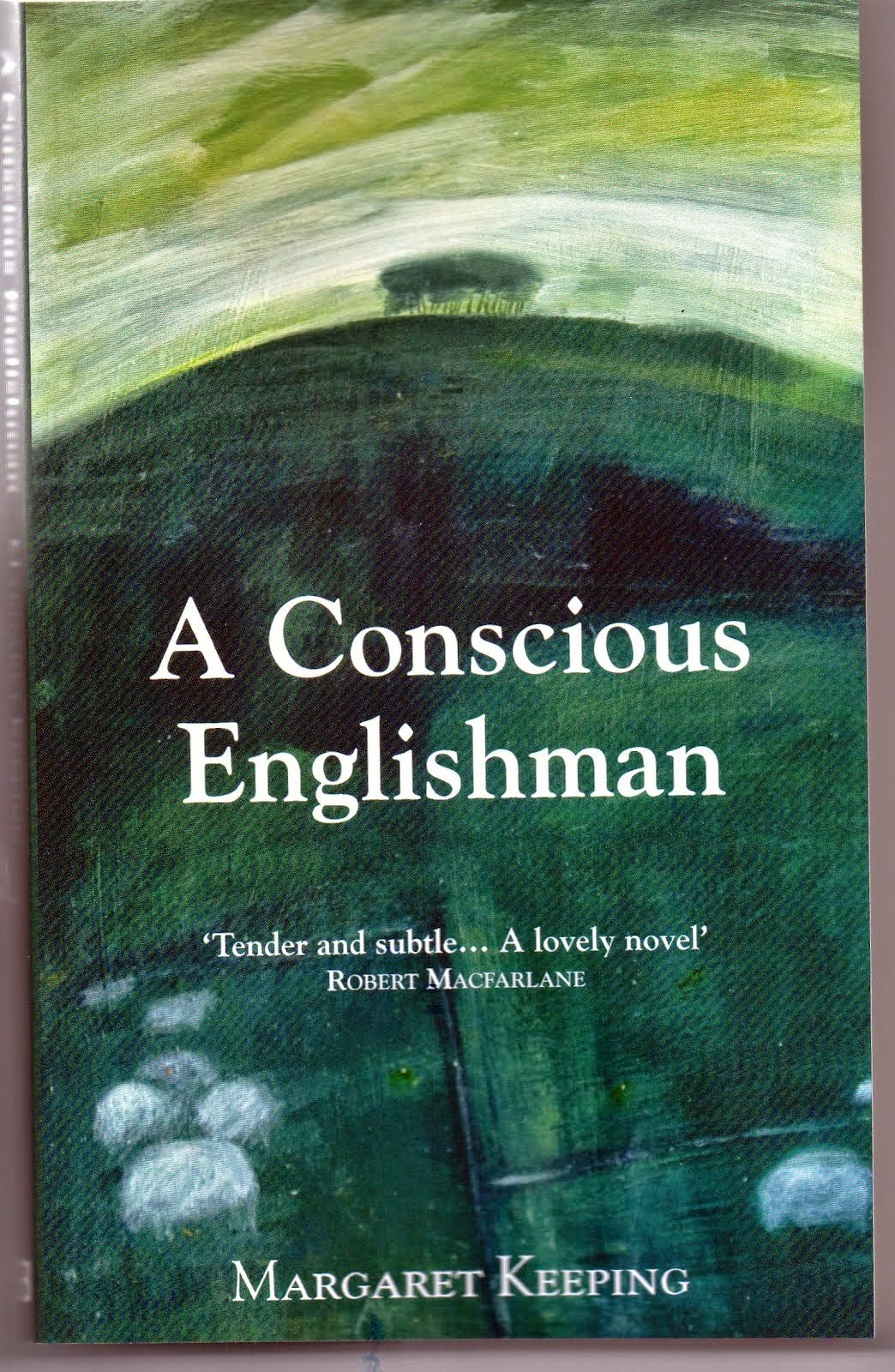

Publishing: A Yorkshire reader sent a very positive message to Frank at streetbooks, and bought two more copies:

'I wanted to say what a fine edition of the book you've published, and I've

enjoyed reading the semi-fictional account of E.T.'s final years. I've been

collecting Thomas's books since I was in the 6th form, and have almost a

complete collection, and so I know a great deal about his life from the

different biographies and collections of letters and memoirs. My wife and I saw

the play in London in January, 'The Dark Earth and the Bright Sky' and we

thought Margaret Keeping's portrayal was more faithful and sensitive to the

actual events. ……….

'A Conscious Englishman' gains from the different narrative voices and

perspectives, and includes many direct as well as oblique references to real

events and to ET's writings. In particular the sections from Edward's

consciousness are well-written and intelligently shaped. I hope the book will

receive some favourable reviews.'

It's pleasing for me to know that readers like this will recognise references and events from the work and life which others will miss - which doesn't matter, but, yes, it's a bonus.

No comments:

Post a Comment